This is the third in a series of posts I am writing in celebration of the bicentennial of my hometown of Greenwood in Oxford County, incorporated February 2, 1816.

The advance and final retreat of the Laurentide ice sheet shaped the landscape of Greenwood, exposing and eroding ancient bedrock and depositing untold tons of sand, silt and gravel within its borders. But it was a more sudden and violent geological process that shaped Greenwood's early history as a town.

The Year Without a Summer

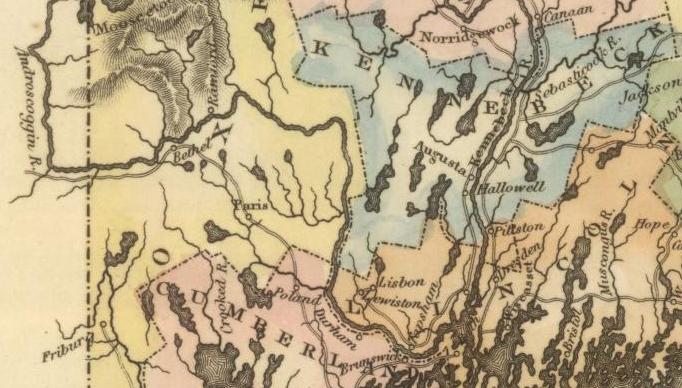

On the Indonesian island of Sumbawa, halfway around the world from Greenwood, rises a volcano named Tambora. Mount Tambora now measures 9,350 feet, but once stood above 14,000 feet. On April 10, 1815, the mountain exploded. The largest observed eruption in recorded history propelled perhaps 38 cubic miles of ejecta into the atmosphere over the course of several days. In January 1816, a months-old letter "from the island of Java" was reprinted in newspapers throughout New England:

A few days since a dreadful volcanick eruption took place in the island of Samboroa, to the eastward, which has been attended with the most destructive consequences. At Sourabaya the atmosphere was in entire darkness for two days, so as to give the appearance of midnight. At this place, which is at a considerable distance, the ashes discharged from the crater fell in heaps. The noise produced from this awful visitation is beyond description, and caused a sensation among the inhabitants peculiarly afflicting. The sea rose six feet above its ordinary level, almost instaneously causing the destruction of many lives, and also vessels.1

This item may well have passed under the eyes of some citizens of Plantation Number Four. News more obviously relevant to their lives arrived just weeks later: An act to incorporate their plantation as the town of Greenwood had been approved by the General Court in Boston and was signed into law by Governor Caleb Strong on the second day of February. It fell upon Noah Tobey to "notify and warn" his fellow townsmen "to Meet at the schoolhouse in said town on Saturday the twenty third day of March instant at Eleven of the Clock in the fournoon [sic]." The men of Greenwood gathered on Patch Mountain at the appointed hour, elected their chief town officers — Paul Wentworth as town clerk, John Small, Isaac Flint and Jeremiah Noble as selectmen, Frederick Coburn as treasurer — filled the minor town offices with qualified candidates, and adjourned. They could not have guessed that their first year as a town would be a year of unparalleled hardship.

Most ash from Tambora had fallen from the sky within eight hundred miles of the smoking crater, but the sulfur dioxide released from the volcano remained in the stratosphere, where it oxidized and formed tiny particles. These sulfate ions circled the globe in the months that followed, reflecting the sun's light back into space and cooling the earth below. So it was that in New England, 1816 was "The Year Without a Summer."

Ransom Dunham — for many years a Baptist preacher in Woodstock — was residing in Paris in 1816, and recalled the year well:

In 1816, June 7th, snow fell 2 inches. I rode from Hebron to Livermore that day on horseback and came very near freezing. It was so cold that it killed the birds; English robins were picked up as well as all kinds of birds, frozen to death. Frost every month that year.2

This weather was confirmed in a story told to Lemuel Dunham by his father, who lived in Hartford:

In June of that year, the late Rev. Daniel Hutchinson was ordained, and the day was so cold that the men shivered with their overcoats on, although several young ladies were dressed in white and seemed resolved to make the best of their situation. A number of slight snow squalls passed over during the day.3

Addison E. Verrill recalled hearing his grandfather Daniel Verrill, who came to Greenwood from Minot in 1818, tell of the "frosty year, 1816, when frost and ice formed during every month, and all the corn and nearly all the other crops were killed."

No corn escaped except rarely on the higher hills. Corn had been planted over and over again, and seed corn became exceedingly scarce and high priced, selling at $4.00 to $5.00; and rye and wheat at $2.00 to $3.00 per bushel. Most of the corn that grew was of no use, except for fodder.4

It was said that "ice formed of the thickness of common window glass" on the morning of July the fifth throughout New England.5 August was no better, with ice to the thickness of half an inch and killing frosts statewide. Deacon William Wentworth of Brownfield — brother of the new town clerk, and himself a former resident of the township — reported "some snow on the 6th, 7th and 8th of June; a frost on the 30th of June, July 9th, and August 22d."6

A Village Born of Fire

For the subsistence farmers of Greenwood, the loss of a year's harvest meant many cold months of hunger, and anxiety about the next growing season. In autumn came added cause for concern. Spring and summer had brought little rain, and fires swept through the forests of Greenwood and surrounding towns. The Portland Gazette reported in early October that "The dryness of our atmosphere is now aggravated by the prodigious quantity of smoke with which it is surcharged."

In the counties of Oxford and Kennebec and from the river Kennebeck to New Hampshire, fire has raged so violently in the woods and soil as to leave scarcely any means of arresting its process. In some places broad trenches have been dug in the earth as the only effectual barrier to its ravages. The smoke in some places is oppressive and almost suffocating, affecting the eyes and lungs most disagreeably.7

Southerly winds brought news of the fires to Boston:

It has been observed here for several days past that the atmosphere has been filled with smoke. It proceeds from a very extensive and destructive fire in the District of Maine. We have not been able to ascertain its extent, with much precision, but we are informed by a gentleman from the neighbourhood of the conflagration, that it extends over a very large tract of country in the county of Oxford, including the towns of Paris, Albany, Hebron, Bethel, &c. and the Northern part of the county of Cumberland, including Minot and other towns.8

According to Dr. William B. Lapham, so extensive were these fires that in Woodstock "ordinary print could be read by their light in almost any part of the town at midnight, and the summits of the blazing mountains could be seen far away." They "not only destroyed the wood and timber, but in places the surface soil was charred and greatly damaged by the intense heat."9 This devastation hastened development in the northern part of Greenwood. As Lapham notes in his History of Bethel, it was as a consequence of these fires that Samuel Barron Locke of Bethel took an interest in the town.

About the year eighteen hundred and sixteen, fires in the woods killed vast quantities of timber which, if not utilized at once, would decay and be spoiled. This induced Mr. Locke to buy a tract of land, and erect mills on the outlet of certain ponds in Greenwood and Woodstock, which outlet has since borne the name of Alder river. These mills have since that time borne the name of the builder and owner, and are situated in Greenwood about half a mile from Bethel south line.10

Locke's Mills would eventually become Greenwood's largest village and the center of town government.

"The hardest winter I ever knew"

Artemas Felt was for most of his adult life a resident of Greenwood — first on Rowe Hill (then called Felt's Hill) and later on Howe Hill. This brutal year he was working for Lemuel Perham Jr. in Woodstock, and was "frequently called upon to help the settlers fight fire to save their buildings."11 Felt was obliged to run for his life one day in October when surrounded by flames, but the next day "it began to rain the first for many months, and the people of Woodstock felt to rejoice like the Israelites of old when Moses smote the rock and the water came forth." The season that followed was, Felt wrote, "the hardest winter I ever knew."

[S]now came on early and deep and averaged six to eight feet on a level. There was not a day during the winter that the snow melted. It was the 20th of April before the warm weather of spring came to our relief. It then came on very hot, and the rugged winter of 1816 and 1817 had disappeared.

Though writing of Woodstock, Felt was describing as well the plight of Greenwood's early farmers:

The principle crop raised in the season of 1816 was rye; there being no fodder and but little hay and no kind of provender to be had, the out-look for the farmers' stock for the winter was gloomy indeed. In consequence of the dry cold season, the stock came to the barn poor, no brouse to be had on account of the fire running through the woods. Many cattle died of starvation. Towards spring food began to grow scarce and as there was none to be had, whole families lived for months, until crops grew again, on milk, fish caught from the brooks, and later upon roots and ground nuts dug from the ground, clover heads were gathered and steeped for nourishment, old cobs were ground up and the meal made into bread, etc., and great suffering was among the people. Men were glad to work for those who had rye to spare for their peck of rye per day.

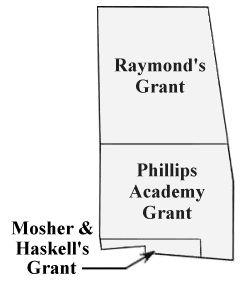

Major Cummings and the Academy Grant

Eleven years after his purchase and one harsh year after Greenwood's incorporation, Major Cummings worried about those to whom he had sold land in the Academy Grant. In the spring of 1817 he bought of David Noyes four bushels of seed corn, which he distributed to the Greenwood settlers. In the next few years, his worries deepened. Cummings had mortgaged the land to the trustees of Phillips Academy in 1806, and he had failed to pay his note. In the interim, he had sold or contracted to sell dozens of lots in the grant, sometimes taking lumber or labor in payment. "Some paid up in full for their lots," David Noyes wrote, "and some had the precaution to insist on his getting an acquittance of their particular lots from the Trustees of the Academy, who held the mortgage; and, to accomplish this, he mortgaged his own farm to them to keep their security good."13 The major's generosity exceeded both his means and his business sense. He had spent proceeds from land sales on other endeavors rather than paying down his debt, leaving him unprepared for the calamitous events of 1816 and their financial aftermath. Cash became scarcer, and purchases of and payments for land slowed. A crisis loomed.

Early in May 1820, Jonathan Cummings went to his barn and slit his throat with a razor. His wife, passing by, found him gasping and bleeding profusely. She bound the wound tightly and called for a surgeon. Cummings recovered, and professed sorrow at his rash act. His creditors pitied him and offered good terms for settling his debt. All thought the crisis past. But sometime in the forenoon of July 12, in the nursery near his house, Cummings severed a jugular vein on the right side of his neck with a jackknife. Having achieved his desperate end, he folded up the knife, and still held it in his hand when discovered. Greenwood's largest proprietor was dead at the age of forty-nine.

Assessing the Damage

In the probate proceedings that followed, the estate of Jonathan Cummings was found to be insolvent. Having not received payment on his note since February 1818, Phillips Academy took final possession of more than half its original grant in June 1823, and in March 1824 paid five dollars for the estate's right to redeem the land.14 Some settlers who had secured deeds from Cummings lost title to their land. Edward Fifield of Durham had paid Cummings $600 for two lots near Greenwood City in 1816. Not until 1835 would he regain ownership of his homestead by paying another $200 to the Academy trustees.15 Those who had taken up lots in the grant but not yet received their deeds were also affected by the foreclosure. The estate file of Major Cummings includes a list of forty-one outstanding promissory notes, many of them signed by settlers in Greenwood who must have contracted with Cummings for land.16 They would have to negotiate new contracts with the Academy, or else abandon their improvements.

These were personal hardships, but the consequences of the foreclosure would be felt more widely in the town. When the Commonwealth of Massachusetts passed "An Act relating to the Separation of the District of Maine from Massachusetts Proper, and forming the same into a Separate and Independent State" in 1819, it provided that "all lands heretofore granted by this Commonwealth, to any religious, literary, or eleemosynary corporation, or society, shall be free from taxation, while the same continues to be owned by such corporation, or society."17 When Maine became a state in 1820, this provision was included in its constitution. The land in Greenwood reclaimed by Phillips Academy could not be taxed.

In 1846, in response to a petition to the Legislature, the selectmen of Greenwood would admit that "as a Town we are Proverbially poor, & that our inhabitants are generally poor." This was attributed in part to the fact that "there are within the limits of said Town, to the amount of almost Three & a half Thousand Acres of Land, upon which no Tax can be assessed — the same belonging to an unincorporated Literary Institution, to wit 'Phillip's Academy.'" The town's topography placed even more land beyond the reach of the assessors:

We would Represent that there is a large amount of Waste & Unimproveable Land, the amount standing on our Valuation Books at 3875 Acres — the whole number of acres within our exterior limits being 24000 acres, which gives a waste of almost one sixth part, which added to the amount belonging to "Phillips Academy" makes almost One third, upon which we can assess no tax.18

The Academy would eventually divest itself of its land in Greenwood, but the damage was done. Greenwood struggled to keep pace with its neighbors through the first half century of its existence.19 This was not due to any deficiency in its inhabitants, but rather, in part, to a volcanic event half a world away that had hobbled the town in its first year of incorporation, driving its largest landholder into insolvency and despair, and ultimately depleting its tax base.

Notes

1Portland Gazette, Jan. 16, 1816.

2William B. Lapham, Centennial History of Norway, Oxford County, Maine (1886), p. 69.

4Addison E. Verrill, "Recollections of Early Settlers of Greenwood," Oxford County Advertiser, Sept. 11, 1914.

5Unattributed quotation, William B. Lapham and Silas P. Maxim, History of Paris, Maine, from its settlement to 1880 (1884), p. 130.

6William Teg, History of Porter (c1957), p. 42.

7Portland Gazette, Oct. 8, 1816.

8Boston Weekly Messenger, Oct. 10, 1816.

9William B. Lapham, The History of Woodstock, Maine (1882), p. 41.

10William B. Lapham, The History of Bethel (1891), p. 135.

11This passage and following from "Narrative of the Hard Season of 1816 and the Winter of 1817," Oxford County Advertiser, April 25, 1884.

12Oxford County, Maine (Eastern District) Deeds, book 12, page 399. Also excepted from the conveyance were a few lots reserved "for public uses."

13David Noyes, The History of Norway (1852), p. 120. Cummings's original mortgage will be found in Oxford County, Maine (Eastern District) Deeds, book 1, page 525. The mortgage on his farm in Norway was dated Feb. 1, 1810 (ibid., book 6, page 253).

14The Academy, through its agent Uriah Holt, took possession of the entire tract on June 5, 1821, and then in late March 1822 took possession of fifty-nine individual lots and half-lots "by actually entering on said lots separately." See Oxford County, Maine (Eastern District) Deeds, book 20, page 163; and book 23, page 122. The Academy's purchase of the estate's right of redemption will be found in book 25, page 18. See also this document from the estate file of Jonathan Cummings.

15Oxford County, Maine (Eastern District) Deeds, book 19, page 10; and book 47, page 389.

16Oxford County Probate Records, Estate Files, Drawer C21. The majority of these notes were dated after the events of 1816, and outnumber the handful of lots Cummings was able to sell outright in the same period.

17The Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (1819), p. 252.

18Box 177, Envelope 26, Legislative Records (1846, Graveyard), Maine State Archives.

19Social Statistics schedules completed at the time of the 1850 census show that the total valuation of Greenwood's real and personal estates lagged behind those of all the towns it bordered. In 1860 and 1870, Greenwood's valuation surpassed only Albany's. Woodstock was wealthier despite the entire township having been granted in early years to educational institutions.These grants passed into private hands before Woodstock's organization and incorporation, and were never foreclosed upon as in Greenwood.