This is the fifth in a series of posts I am writing in celebration of the bicentennial of my hometown of Greenwood in Oxford County, incorporated February 2, 1816.

Greenwood had from its early days its own militia company made up of able-bodied townsmen between the ages of eighteen and forty-five, each supplying his own weapon. "May training" was held each year in a field near Greenwood City, offering the citizen soldier an opportunity to shoulder his musket and share in the company's provision of sweetened rum. More drills were held in September, in preparation for a regimental muster, perhaps at Paris or Norway. The militia system was abolished in 1844 and a new system introduced that required enrollment, but no active duty except at times of public emergency. On the eve of the Civil War, Oxford County had thousands of men enrolled in the militia, but only one active company: Norway Light Infantry.

The First Volunteers

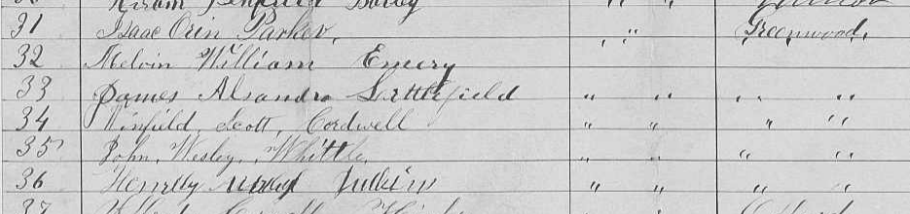

On April 15, 1861, a day after the surrender of Fort Sumter, President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to defend the nation's capital. Maine was to form one regiment to serve for ninety days. So stirred to action were the state's citizens that enlistment rolls swelled. New companies rapidly formed, but could not be received into the First Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment, preference being given to existing units. The regiment did include the Norway Light Infantry company, renamed Company G and fortified with enlistees from surrounding towns. Seven men from Greenwood responded to this first call to arms: Winfield S. Cordwell, Melvin W. Emery, Henry N. Judkins, James A. Littlefield, Isaac O. Parker, Francis E. Shaw and John W. Whittle. George W. Patch of Greenwood had been second lieutenant of the company, but resigned his commission before it was mustered into federal service.

Decades later, William W. Whitmarsh described the company's departure from Norway:

"The company had proceeded down the Main street to where used to stand the old Horne Tannery, which was destroyed in the big fire years ago. Everybody who was able wanted to go to war in those days," recalls the captain. "As we reached this point and the band was playing war songs, a man burst thru the crowd and demanded to speak with the captain. He asked permission to join the company and offered $25 to any man who would sell him his place. But in 1861 every man of us was proud to go to the front and no one would sell."1

The company was mustered in at Portland on May 3. Governor Israel Washburn Jr. had a week earlier informed the Secretary of War that the men would be "impatient to move."

They can go by rail or steamer. There are good steamers to be had at Portland. Two or three regiments may be in readiness in ten days. The ardor is irrepressible.2

Despite the governor's promise, the First Maine was detained by an outbreak of measles for a month. The Oxford Democrat reported on May 17 that Privates Parker and Emery from Greenwood were among those hospitalized. On June 1 the regiment embarked for Washington, D. C., where they encamped on Meridian Hill for two months. They returned to Maine at the height of summer, and on August 5 were mustered out at Portland. The First would be reorganized as the Tenth Maine Infantry in September, with many more Greenwood men joining its ranks.

Captain Houghton's Company

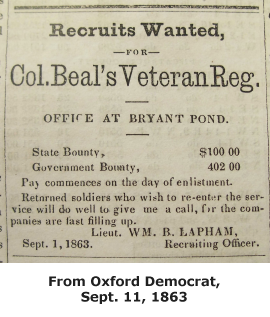

An act approved in Augusta on April 25 authorized the organization of nine additional regiments of volunteers, to serve for two years (later extended to three). A company was raised in Greenwood, Woodstock and other towns by order of Major General William W. Virgin of Norway, to be quartered and trained at Bryant's Pond. Dr. William B. Lapham recruited the company, though this did not lead to the commission he sought.

I received the recruiting papers and returned to Bryant's Pond. Notice was given through the Oxford Democrat, and by posters, and men came in about as fast as I could enroll them. In a few days I had two-thirds of a company in camp, and it became necessary that they should be drilled. I had never had any experience in military affairs, and not one who had been enlisted was competent for a drill-master. In this emergency, I made arrangements with Moses Houghton of Greenwood who had been a captain in the old militia, to take charge of the company. He could not do this without compensation, and so we arranged that he should be elected captain and fill that position until the regiment should be ready for muster into United States service, when he was to retire, and I was to succeed him. Mr. Houghton was passed middle life, and his health had become so impaired that he did not think it prudent for him to go into active service at the front.3

The election of officers occurred on May 6, with James Russ of Woodstock chosen first lieutenant and Stephen Estes Jr. of Bethel second lieutenant. The next day Moses Houghton reported to Adjutant General John L. Hodsdon that "I have been elected Captain of the Company recruited at this place and as it seems probable we may be here sometime, I think we could make better progress if we could be furnished with arms."4 He suggested that the state arsenal in Portland could supply their needs, and requested also "a fife & drum and a copy of Hardees Tactics." On May 11 Houghton reported that the company "not having orders to march to Portland are deficient of camp utensils," and requested guidance on how to proceed.

The expense of Keeping the Soldiers here is about three Dollars per week thus far. Therefore it is absolutely necessary that we should have matreses or such for lodging the Soldiers.5

By Friday, May 17, the captain had trained his enlistees without proper equipment for nearly two weeks. "We have been expecting Guns," he reminded Hodsdon, "and have not receved [sic] any, nor Fife or Drum, the Fife and Drum that we had were borrowed and are called for."6 In a postscript, he stated that "We think we can report ourselves full next Monday." That same Friday, the Executive Council in Augusta resolved that the companies "already formed and organized by the election of officers, under the act of April 25, 1861," were "more than sufficient to make up the number of Regiments which it is believed will be accepted by the United States from this State, for a considerable time to come, if ever."7 Maine would create only six regiments, filled with companies already organized. Any hope that the company at Bryant's Pond would be attached to one of these six regiments was dispelled the following week, with the issuance of General Order No. 27.8 At eleven a.m. on May 28, less than a month after its formation, Houghton’s company was to be mustered for payment at Woodstock and choose one of three options: take a leave of absence without pay or rations until called back into service; commit to no more than two days per week of drills and instruction "without quarters or subsistence" and be paid pro rata; or disband.

The Oxford Democrat of May 31 reported the company's decision:

No one was more dissatisfied than William B. Lapham, who had spent a month drilling and studying tactics, only to lose his chance to lead the company he had recruited into battle. In a letter to the adjutant general that fall, he blamed the company's decision to disband on James Russ — "a man of doubtful patriotism."9 "He broke up our Company last spring," Lapham alleged, "& had he been away it all should have gone into the 5th Regiment." Writing to Governor Washburn two days later, Lapham said of Russ that "his sympathies were openly expressed for the South until some time after the conflict had commenced," that he "would rather raise recruits for our enemies," and that "as a politician, he has ever been a viper — just the antipodes of what his brother Horatio is, whom, I presume, you well know."10We learn that the company at Bryant's Pond disbanded on Tuesday. Seventy-one privates were paid off. A part of the members have gone to Portland, to fill up the Bethel company. The roll of this company was filled up earlier than that of Bethel, and much dissatisfaction is felt, that it was not attached to the fifth regiment.

The final roll for Houghton's company, dated the day of its dissolution, included the names of thirteen privates from Greenwood: John A. Buck, Joseph Cummings Jr., Woodbury Cummings, Solomon Farr, Daniel Grant, George Howe, Robert Howe, Elijah Libby Jr., Royal T. Martin, Charles F. Morgan, Jacob W. Morgan, John M. Swift and Augustus H. Swan. The captain's eldest son, Charles R. Houghton, had been a servant to the company.11

Several of these men promptly enlisted in Company I, Fifth Maine Volunteer Infantry, formerly the Bethel Rifle Guards. Daniel W. Grant, George G. Howe, Robert Howe, Royal T. Martin, Charles F. Morgan and Jacob W. Morgan were mustered in June 24 at Portland, joined by fellow Greenwood resident Joel W. Brackett. The youngest child of Thomas P. and Caroline (Eaton) Martin, Royal Thomas Martin would never again see his home and family. Within weeks he was discharged by reason of disability, and on July 24 — one week shy of his eighteenth birthday — he died in Washington, D. C. Royal was the first of Greenwood's war dead, but the Martins would not be alone in mourning a son's tragic end.The Home Guards

Captain Houghton wrote to the adjutant general as summer approached, seeking permission to rebuild his company.

Having learned that the two Regiments now under organization are about to be mustered into the service of the United States and that it is the intention of the Governor to Keep two in readiness I would thus inquire if it is his intention to give to the Officers of those discharged companies new enlisting orders and allow them the privilege of serving their Country that they would of [sic] had if they had not been discharged.

As our Company was organized before some others were that went into the fifth regiment we would like that our Officers would be empowered to enlist enough to make a full Company with what have not gone into other Companyes.

We have made arrangements to have the soldie[r]s boarded for just what their rations are per day except their Lodging which is all ready prepared in their Barrack that they used before. I think if our Officers in this company are empowered now to enlist, we can procure a Company in ten days after commencing. I should be Glad to have an answer as soon as convenient for the Haying season will soon commence and it wil be more difficult to procure them.12

Captain Houghton would not be asked to raise another company for possible federal service, but within a month he was commanding a company of Home Guards.

Maine's militia law had been amended in April to require additional duties of the state's volunteer companies of enrolled, "ununiformed" militia, and to provide for their compensation. Implementation of this act, though, was “suspended almost entirely” in order to maintain the supply of volunteers for "actual service."

The claims of the various localities for these home organizations, were pertinaciously urged, and any principle that would admit one, would, of course, admit all. This would devolve such an amount of labor and attention to details upon the commander-in-chief, the executive council and the military officers of the State, in the organization of these proposed companies as would have materially interfered with the duties they owed the general government in responding to the requisition of the President for troops.13

In his history of the Seventeenth Maine Infantry, Red Diamond Regiment, William B. Jordan wrote that the enrolled militia would be judged to have "contributed very little, having disintegrated into a pandemonium of drums, gingerbread, and rum."14 While his opinions on gingerbread and rum went unrecorded, we do know Captain Houghton's thoughts on drums. He had in July 1861 come into possession of a drum belonging to the state, and formerly used by the Norway company. Norway had procured a new one, and Houghton wished to retain its castoff.

I was ordered last evening to give it up to the Bethel Home Gards a Ceession Company as I expect that you understand [v]ery well, we have a good Company of home Gards here which are not Ceessionest and are at the service of the State if they are wanted[.] I should like to ke[e]p the drum and will be accountable for it if it is your pl[e]asure.15

The Bethel Home Guards had been organized by Gideon A. Hastings, who was a Democrat and thus vulnerable to accusations of Southern sympathies. A letter published in the Oxford Democrat that summer shows what dark threats an actual secessionist might have faced:

Locke's Mills, July 22, 1861.It is well known that the flag raised at this place two months since, is threatened by a secessionist who has been reading the "Day Book," and poisoning his already weak mind, with "black Republican slanders," and lies which make up that paper. Let him make the attempt to burn that glorious flag, and bring to his assistance as many of the rebels as he can find. The sooner the better; and I will warrant him the same inglorious end that awaits all pirates sailing under Jeff. Davis, for whom he has so much respect that he even refuses to attend church, because the minister in referring to the traitor didn't call him President, instead of Jeff. Come on, traitors, and do your work — your doom is sealed.

This is the voice of

MANY PATRIOTS16

Captain Houghton was promoted to Colonel by the end of the summer, in command of the militia regiment to which his former company had belonged. The Portland Daily Advertiser reported on September 7 that a "company of Union Guards was formed at Bryant's Pond last Friday" — possibly a successor to Houghton's company of Home Guards. A day earlier had come news of another company assembled in the same town.

A company of cavalry was organized at Woodstock, on Tuesday last. The officers chosen were: Joshua S. Whitman, of Greenwood, Captain; John Day, of Woodstock, 1st Lieutenant; E. M. Hobbs, of Woodstock, 2d Lieutenant; Dustin Bryant, of Greenwood, Cornet. Forty-two men have enrolled themselves already, and more are ready to join. The company is made up from the towns of Woodstock, Paris, and Greenwood.17

Whitman and Day had nearly twenty years earlier held the same positions in a cavalry company that "sometimes met for drill on the level land between West Paris and Trap Corner."18

While the adjutant general could provide them little support, he appreciated the enthusiasm with which the ununiformed volunteers committed themselves to their training.

Notice of a "Volunteer Regimental Muster" appeared in the Democrat of September 20, signed by Moses Houghton, "Colonel Commanding." It was to be held on the Common at Bethel Hill, October 8 and 9.Informal volunteer associations for military duty have been numerous in various parts of the State, and during the last fifteen years, there has not been seen such an array of citizen soldiery parading for discipline and review, as was witnessed in the months of September and October of the present year; and this not only without compulsion, but after repeated refusals to their applications for organization.19

An invitation is hereby extended to all volunteer companies in this vicinity to be present and take part in the exercises of the field.

The two-day encampment and muster began on a rainy Tuesday, with companies attending from as far as Island Pond, Vermont, and as near as Bethel, which was represented by three.

On Wednesday morning, the sky was without a cloud, and the military spirit was fairly aroused. The Common was soon covered with companies, marching and countermarching, to bring themselves into the best possible condition. At ten, A. M., the companies were formed into line by the Acting Adjutant Lieut. Wormell, who is on a furlough from Washington. After going through the dress parade, they were formed into platoons, under the command of Col. Moses Houghton, assisted by Lieut. Col. G. A. Hastings and Maj. G. A. Robertson.

The Bryant's Pond Light Infantry company under Captain Perrin Dudley "made an excellent appearance in their tasty uniform and have an experienced officer in command."

A sturdy looking company of cavalry from Woodstock, Capt. Joshua S. Whitman, went through their peculiar tactics quite successfully. Their Captain knows how to ride a horse.20

Major General Virgin and his staff performed an "informal" review of the troops, and were pleased. Recruiting officers in attendance enlisted many for the war. The companies voted to meet again on Bethel Hill on the first Saturday of November. Seven companies were present at this next muster, and "made a very neat appearance."

In the afternoon, the Bethel Zouaves, under Capt. True, spent an hour or two in the skirmish drill against a cavalry company, under Capt. Whitman, of Woodstock. The maneuvers were repeated with great rapidity, and the exercise was highly enjoyed by those engaged in it.21

These public displays brought back memories of the old militia days, and even employed some of the same actors, but they would not last. The war raged on, and the Union cause could spare no able-bodied volunteer.

A Prompt and Patriotic Response

The Confederate rout at Bull Run in July 1861 made clear that the rebels would not be easily defeated, and that additional Maine infantry regiments would be necessary after all. A general order dated July 27, 1861, commended Maine troops for the valor displayed at Manassas, and called upon the men of Maine "to emulate the patriotic zeal and courage of their brothers who have gone before them."

Having already contributed generously of the flower of her youth and manhood, Maine must send yet more of her stalwart sons, to do battle for the preservation of the Union, and for the supremacy of Law.

To this end, the Commander-in-Chief had directed the enlistment of additional Regiments of Volunteers, and doubts not that his call will receive a prompt and patriotic response.22

Greenwood's quota that fall was twenty-two men — a number it would meet and surpass.

When the Ninth Maine Infantry Regiment was mustered in at Augusta on September 22, three sons of Joseph F. and Martha (Morton) Emery of Greenwood were included in Company F: Joseph Freeman, James N. and Melvin W. Emery. Melvin had served and been mustered out with the First Maine, and was appointed first sergeant soon after his reenlistment. He would die at Fernandina, Florida, in 1862. His brother James would be killed in action at Fort Wagner, Morris Island, South Carolina, in 1863. Franklin Q. Dunham, a machinist residing in Greenwood, was mustered into Company F as well. He would be shot through the head and killed at Cold Harbor, Virginia, in 1864. Frank's parents, James and Sally (Houghton) Dunham, had come to Richardson Hollow in 1859, and would return to West Paris a year after their son's death.

A member of Company F wrote to the editor of the Lewiston Journal in October:

The company as I have already intimated is made up of Oxford Bears. Thirty are from the town of Sumner, some twenty are from Paris; Canton, Peru, Greenwood, Hartford, Woodstock and Dixfield furnish the remainder, with the exception of about half a dozen from Franklin County. The great majority of the men are intelligent farmers; they are wanting neither in muscle or resolution, and should the regiment be called into action, I trust they would cast no disgrace upon the land of their birth.23

An additional six men would enlist from Greenwood in Companies F and G of the Tenth Infantry Regiment, mustered in the first week of October: John A. Buck, Consider Cole, Elijah Libby, William H. Pearson, Benjamin Russell Jr. and Nelson R. Russell. Buck became ill "while going out, by eating a poisoned cake," but made a full recovery.24 All of these recruits would return home safely but one: Consider Cole would die of disease at Alexandria, Virginia, just days before Lee's surrender at Appomattox.25

Three Greenwood men enlisted in the Thirteenth Maine Regiment in October 1861 — Kingsbury J. Cole, Joseph Cummings Jr. and Cyrus Swift — and were mustered in at Augusta in December. Their service records illustrate the dangers faced by soldiers even far from the battlefield. The Thirteenth Maine rendezvoused at the United States Arsenal in Augusta, where the number of tents was found to be insufficient, and the "floors barely furnished sleeping room for the number of men required to occupy them."26 Cole became ill after joining his company in these close quarters:I enlisted the 24 of Oct went to Augusta. By exposure there Contracted A disease of the lungs. was Confined In the Hospitle some three or four Weeks.

Cole was given a furlough of eight days, and obtained a "Certificate from Drs. Grover & Wiley of Bethel of my inability to Return."

When I enlisted my family was dependent upon my labor for Support By exposure at ... Augusta. I lost my health which my physician thinks I shall not recover very soon if ever.27

Cole was subsequently discharged for disability.

Joseph Cummings also fell ill in Augusta, from rheumatic fever. He was given furlough and when the regiment's date of embarkation was announced, he was not called for. He was reported deserted, and never rejoined his company. Cyrus Swift survived his stint in Augusta, but died from "continued fever" contracted while in the service, August 28, 1862, at Fort St. Philip, Louisiana.28 Swift's widow — Joann P. (Jordan) Libby after her remarriage — was for many years a resident of Locke's Mills, as were his sons Nelson and Walter.

In addition to those joining new companies, several men enlisted in the fall of 1861 in companies already formed, but whose numbers had been depleted. Lory N. Fifield, Lithgow L. Hilton, George W. Libby, George M. Littlefield, Peter Jordan Mitchell, Austin W. (alias Thomas A.) Morgan, David Morgan, Edwin Morgan, George W. Morgan, Jacob V. Morgan, Osgood Morgan, Otis E. Morgan, Samuel Morgan, John M. Swift, William Whitman, Moses M. Whitney and Cornelius M. York all joined companies in the Fifth Maine Regiment. (Six more men would join the Fifth Maine in early 1862 on Greenwood's quota: William G. Cole, George W. Davis, Dana B. Grant, Abner H. Herrick, Stephen D. Knight and Albert A. Trull.) The Democrat of December 20 reported that "The company of volunteers recruited by Capt. Patch, of Greenwood, has been filled up to the army standard, and will be attached to the Maine 5th. The company left for Washington, Monday." To George W. Patch's credit, his own name appears first on the enlistment roll. He had resigned his commission with the Norway Light Infantry before it was mustered into the First Maine, but reenlisted in November and was commissioned captain of Company G, Fifth Maine Infantry, in January 1862. He would be furloughed and then resign his commission the following June, his family having suffered financial losses with the destruction by fire of Greenwood City.

The Morgan families of Greenwood would suffer even greater losses. Of the eight Morgan men sent off to war in 1861, three would die within a year, and a fourth would be discharged for disability and die less then two years after his enlistment. The official records say that George W. Morgan died of angina pectoris at Harrison's Landing, Virginia, but in a deposition in support of his mother Drusilla's pension application, cousins Otis E. and Charles F. Morgan asserted that he died of chronic diarrhea contracted in the service, "aggravated and made much worse by the climate and his food, being for a considerable portion of the time, fresh beef, not being able to procure salted meats, that for six of eight weeks before going into the Regimental Hospital, he tented with Otis E. Morgan, aforesaid, and that during all this time, he had to go out nearly every night, from two to six or eight times in a night, in consequence of said Diarrhea, and we could plainly see that he was growing weaker and failing daily."29 In a letter to his wife dated August 8, 1862, Lory Fifield wrote that George, despite his debility, "was so that he could wauk around the day he dide."30

Samuel Morgan was also reported to have died from angina

pectoris, but an officer in Morgan's company deposed that the true cause

was typhoid fever "brought on by exposure and fatigues incident to the

service during the peninsula campaign under Genl McClellan."31

Lory Fifield reported only that Samuel had "bin sick sum time."

Samuel's brother Osgood would die of fever in October, leaving their

soon-to-be-widowed mother Sarah to collect a pension as the mother of

two fallen soldiers.

Lory Fifield's letters home to his wife Sarah tell the tale of one other soldier's decline.

[From Mechanicville, Virginia, June 7, 1862]

I've fath as tho this war would close soon. if so if god should spare my life i can go home to see you. Wee expcts to go into Battle every hour and I think that this is in a Battle wee all shuld have to fite at, and I hope it will be for I want to git home. I am tiard of war.[From Harrison's Landing, Virginia, Aug. 8, 1862]

I sopoes you think [it] s[t]range that I du not rite to you know oftener. if you new how it was you would not blame me much. wee have had a hard time of it this summer.[From hospital at Newport News, Virginia, Aug. 25, 1862]

Wee started on a three days march and I was taken sick to the hospitile but I feel better now and am in hopes i shall be able to go to my regment in afu days.[From hospital at Newport News, Sept. 22, 1862]

I tak this time to inform you of my helth wich is beter than it has bin for sum time Past and I am in hopes [to] soon be weal again. I think if I cold have sum of your good cak and buter and good thints to eat I should git well in afu days, but our living is poor. [He describes the hospital's uninspired menu.] this is our living ever day and you must spose that I should get sick of such living as this, but I feele as tho wee should soon git out of this and have our lebirtry once more.

Fifield was discharged for disability in early October, but died from chronic diarrhea at the Soldiers’ Aid Asylum in Philadelphia before reaching home.

The Bounty System

Near the end of 1861, the War Department instructed Maine’s governor to "go on with the organization of your troops as usual, but do not let any more leave the State until otherwise ordered."32 In April 1862, in response to positive news from the battlefields, Secretary of War Stanton discontinued recruitment. General Order No. 11, issued by Maine's adjutant general on April 3, required that recruiters "suspend enlistments, close their several offices and rendezvous, and all unsettled business connected with that service."33 The respite was short-lived, for a month later the governors of Maine and twelve other states were instructed each to "Raise one regiment of infantry immediately," and to "Do everything in your power to urge enlistments."34 Governor Washburn recognized that the patriotic fervor of 1861 had waned, and responded within a day with a suggestion.

I will set about the regiment instanter. Shan't I arrange to [pay] one-fourth of the bounty in advance? It will help amazingly.35

The federal government had provided bounties to enlisted soldiers of $100, payable at discharge. Payment of bounties had become, with the dearth of fresh volunteers, crucial to meeting state and local quotas, and delaying disbursement would no longer suffice. In July 1862 the government relented, and allowed that $25 be advanced to three-year men upon mustering in. The same month, Maine increased its state bounty from $30 to $45 for recruits into new regiments, and from $35 to $55 for recruits into existing regiments.

Greenwood voted in July 1862 to provide a bounty of $60 per soldier after mustering in. This was changed in August to $20 per soldier as a bounty, and a present of $80 when mustered in. The distinction between a "bounty" and a "present" was dubious, but was drawn for a reason. General Order No. 32, issued August 16, proscribed giving bounties of more than $20 to men who volunteered for only nine months' service.36 The voters of Greenwood evidently did not agree, and chose to give equal rewards to their three-year and nine-month men.

Bringing Order to the Militia

"The militia of the State has no organization of any worth," Governor Washburn informed the Secretary of War in May 1862, but efforts were underway to change this.37 "An act to enroll the militia of the State of Maine" had been passed in March, and by its authority Major General Virgin appointed Edmund Curtis orderly sergeant in Greenwood. Curtis was to enroll all the available militia in the town, and to act as temporary commander of the resulting company until a commissioned officer could be qualified. The initial enrollment for Greenwood under this act was 124.

By order of the adjutant general, and under the direction of Major William P. Frye, Sergeant Curtis called out Greenwood's company for the election of officers on the afternoon of Monday, July 14, at Bryant's Pond. The officers chosen were Leonard A. Carter, captain; Lafayette French, first lieutenant; Francis E. Shaw, second lieutenant; Samuel N. Young, third lieutenant; and Octavius K. Yates, fourth lieutenant. It was intended that, after the election of officers, two regiments of militia would be organized in each of Maine's three divisions. This was soon determined to be impracticable. Nevertheless, the enrollment lists compiled and periodically revised by the orderly sergeants would be used in recruitment, in determining quotas, and in conducting drafts in the months and years ahead.As Maine worked to reestablish its militia system, Congress debated an updated Militia Act that would give the president the power to call up state militia to federal service for up to nine months. The act, signed into law on July 17, 1862, brought significant changes to the way men were brought into the army. Where once the states had retained control over enlistment, the federal government now threatened to step in if states failed to meet their quotas. In practice, this allowed the institution of a draft — a noxious concept to many Mainers.

President Lincoln had called for 300,000 additional men for three years' service earlier in the month. Maine's quota was 9,609 men, which placed on individual towns the requirement to raise ten-and-a-quarter men per thousand residents. In Greenwood this came to nine men. Willard O. Ames, Dennis W. Cole, Woodbury Cummings, Solomon Farr, William Gannon, Nathaniel LeBaron and Elisha S. Wardwell were soon mustered into the Seventeenth Maine Infantry. Dana B. Grant, who had served briefly with the Fifth Maine earlier in the year, reenlisted and served in the Seventeenth as well. Franklin Buck, a wheelwright from Locke's Mills, joined the Sixteenth Maine. A call for nine-month men in August, of which Greenwood's quota was only four, was satisfied by four enlistments in the Twenty-third Regiment: William Berry, Israel F. Emmons, Calvin Richardson and Enoch D. Stiles. By meeting its quota, Greenwood escaped the draft of September 10, 1862, as did every other Maine town and city.On the day of the threatened draft, several other men from Greenwood — including Orrin S. Bisbee, George C. Cole, Daniel W. Grant, Lyman R. Martin and Charles H. Milliken — enlisted in Company E, Twenty-seventh Maine Infantry, each claiming residence in the town of Wells. The general order under which the draft was to be held stipulated that a town could furnish volunteers to partly satisfy its quota "provided that they are residents of the city, town or plantation furnishing them."38 This stipulation would explain why these Greenwood men suddenly became residents of a town in York County. It is probable that, like Greenwood, Wells provided each of its nine-month volunteers a $20 bounty plus a generous "present" upon mustering in.

Charles H. Milliken, in his application for an invalid pension filed a year later, stated that he "took a severe cold, while doing picket duty, near the Potomac River in January last, which cold settled on his lungs, causing a severe cough and much expectoration, which still continues."

He also suffers from Chronic Diarrhea, which attacked him since the cold and cough, and is still severe, rendering him unfit for any labor at all, and hardly able to take any exercise, except to ride occasionally in pleasant weather.39

He died from his ailments November 20, 1863, in Greenwood, leaving a widow and young daughter.

Illness kept Dennis W. Cole of the Seventeenth Maine from completing even a month of service. He was discharged at Philadelphia on September 6, 1862, having been "greatly afflicted with a disease of the heart." Upon his return to Greenwood, he was accused of desertion by suspicious townsfolk. Storekeeper Jeremiah Bartlett reported to the Adjutant General on September 20 that Cole was "at home riding round as large as life, sporting on the bounty money" he had received from the town and state. Bartlett felt it was his duty to report Cole, for fear that he would "skedaddle to Canada or somewhere else, as he is a full blood secesh and all his family ditto."40

Moses Houghton took matters into his own hands, which resulted in Cole bringing suit against him in 1864:

[T]he said Houghton on the first day of October A.D. 1862 at said Greenwood, with force and arms assaulted the plaintiff and then and there him did beat and ill treat and arrested and restrained him of his liberty and with force and arms removed him from his house and friends in said Greenwood against his protestations and consent and transported him to Augusta in the County of Kennebec and then and there confined him and compelled him to sleep in an unfinished building upon the floor without any bed clothes or other covering over him, and then carried him before John Hodsdon, Adjutant General of the State of Maine, under pretence that he was a deserter from the army of the United States.41

Cole asked for $500 in damages, but was awarded $50.

The Draft

The Enrollment Act of March 1863 brought about the national conscription system that Congress had threatened with the Militia Act. Men aged twenty to forty-five years were required to be enrolled, with a draft authorized wherever quotas were not met. A drafted man could pay the government a commutation of $300 in lieu of service, or pay a substitute to serve in his place. Charles E. Dwinell would enlist in the Twentieth Maine in August 1864 as a substitute for Joseph Dane of Kennebunk. The selectmen requested shortly thereafter that Dwinell be credited to the quota of Greenwood, as he was a resident of that town when he enlisted.42 Reuben D. Rand of Lisbon, a future resident of Locke's Mills, paid an Irish fellow named William Ryan to serve in his stead. Ryan joined the United States Navy and, like many substitutes, deserted a few months later.

The patriotism and martial spirit that had motivated men to enlist in 1861 were now tempered by a grim awareness of the true nature of war. News of the victory at Gettysburg in July 1863 was undoubtedly met with cheers in Greenwood, but its cost would soon become apparent. Willard O. Ames was wounded in both legs the second day of the battle, and died three weeks later at Jarvis General Hospital in Baltimore. Those who have stopped at the Ames Cemetery on their way to the Greenwood Ice Caves will have noticed the stone engraved with the circumstances of his death. First Sergeant Isaac O. Parker was wounded as well, and succumbed to his injuries just days after Lee's retreat. He had been among the first to enlist from Greenwood, but had reenlisted with the Seventeenth Maine in 1862 from Kittery, where his parents had resettled. Solomon Farr was wounded in the head at Gettysburg, but survived and rejoined his company. In May of 1864 he would be killed in the Battle of the Wilderness. His widow, Elvira J. (Cole) Farr, would marry Ransom Cole of Shadagee.

The first draft in Maine's Second Congressional District under the Enrollment Act was held in Lewiston on July 15, 16 and 17.

It was done in this way: After the lists had been made, the names belonging to the first class in each sub-district, were written on small pasteboard cards, and sealed up in envelopes. When orders were received to proceed to make the draft, the seal containing the names of the first sub-district, was broken, the cards counted, and placed in a cylinder, about 18 inches in diameter. This when closed was turned, by which the cards were thoroughly mixed. Dr. Garcelon, who was blindfolded for the purpose, then opened the little door and drew out a card. This was handed to Commissioner Perham, who announced the name; and a Clerk recorded it as the first man on the rolls, for that district. The box was closed and turned, and the process repeated.43

Greenwood was the thirty-ninth subdistrict, and its turn came the morning of Friday, July 17. The names of all of those enrolled in the first class (which included every man above the age of twenty and below the age of forty-five, excluding married men above age thirty-five and anyone in the service on the day the Enrollment Act became law) were placed in the "wheel of fortune," as it was dubbed, and one by one names were selected until Greenwood's quota of twenty-three was filled.

Drafted men were to be officially notified within a week, but no doubt most learned of their selection within a day or two. Then would come efforts to claim exemption and, for those denied, the payment of commutations and the hiring of substitutes. Exemptions were granted to the disabled, to the sons of widows or aged and infirm parents, to the fathers of motherless children, and to those with two members of the family already in the service. Drafted men from Greenwood were to report to the provost marshal's office for examination on or before Friday, September 4. The Lewiston papers published the results of each day's medical examinations. Lyman R. York was declared exempt for having a "disease of the heart." Charles B. Brooks was found to suffer from an inguinal hernia. Stephen L. Poole and George W. Caldwell both were afflicted with "feebleness of constitution." Octavus J. Cole had a malformed right hand. Another dozen draftees were exempted for unnamed disabilities. Woodbury Cummings was made exempt upon the request of his father, who was dependent upon his support. Forty-one and married, William Whitman should not have been entered into the draft lottery at all. Only three men were reported to have passed their examinations: George W. Record, Ebenezer E. Russell and Solon O. Ryerson. The adjutant general's office would list only Record and Russell as having entered the service.

Ebenezer E. Russell was the son of Benjamin and Mahala (Wright) Russell, who had come to Greenwood from Bethel before 1837 and settled at the lower end of what is now the Irish Neighborhood. His brothers Benjamin and Nelson had previously enlisted from Greenwood, but their terms had expired by the time of Eben's conscription. Russell was mustered into Company B, Third Maine Infantry, and later was transferred to the Seventeenth Maine. Having suffered a spinal injury that left him partially paralyzed in his left leg, he was discharged for disability in January 1865, and a few weeks later applied for a pension. The three brothers, with their parents, would move to Missouri after the war.

George W. Record was an orphan, raised in Greenwood from infancy by his grandparents John and Hannah Noyes. Harry A. Packard offered a touching but apocryphal description of young George's conscription:

It was a sad scene in the humble cabin that dark, cold, autumn evening when two soldiers in uniform came for the young man — there were tears — parting — then the grim demands of war were satisfied. The boy was too feeble to be of any real service to the army. The record was made complete shortly afterwards; he died of disease and was buried in Alexandria, Va.44

The tears, at least, were real. John and Hannah had already experienced loss, their son Fairfield K. Noyes having enlisted in the Second New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry early in the war and died at winter quarters in Budd's Ferry, Maryland, December 16, 1861. George presented himself for examination in Lewiston on August 31 — four days earlier than required, and four days before Eben Russell appeared — and was accepted. The application for George's military gravestone, erected in Richardson Hollow Cemetery in 1897, states that he died in June 1865, and that he served with the Seventh Maine Infantry. The adjutant general's records, however, while indicating that he entered into service, provide no further record of him.

Greenwood voters on March 7, 1870, passed over an article "to see if the town will vote to pay E. E. Russell & Solon O. Ryerson one hundred dollars each as drafted men durin [sic] the late war." Ryerson — another orphan, raised by siblings Asa and Polly Paine in East Greenwood — is listed in state records as having paid a commutation, and never entered the service. The warrant article had meant to reimburse him for a portion of his commutation.

The task of sending its sons to war weighed heavily on Maine's elected leaders, and most heavily on the selectmen of the state’s smallest communities. Many towns were hard-pressed to enlist enough men, some having to bid against wealthier towns for the opportunity to recruit their own citizens. Greenwood suffered this plight in 1863 — not for want of good men, but for want of good timing. The town had more than satisfied its requirements under previous quotas — so much so that now most of its eligible men were already on the battlefield. A disproportionate number of Greenwood’s men had enlisted by the time the draft was imposed, and Greenwood wished to supply no more by compulsion. A reasonable request was made of Governor Coburn by a selectman of the town:

Lockes Mills, Greenwood. Augt. 5. 1863Hon. Abner Coburn

Dr Sir. A matter in which this town is deeply interested, in relation to the draft, has been presented by Mr Herrick Davis of Woodstock, employed by us, to the Adj. Genl. who treated Mr Davis very cavalierly, and said that nothing would be done about the matter.

The Town of Greenwood with a population of about Eight hundred (800) inhabitants, has already furnished seventy four (74) men, which is 27 more than her quota, and now after being nearly depopulated, we are called upon for 23 more, or 2/3 of that Number of sound men. We ask that justice may be done us, as it is in larger towns in Massachusetts, like Nattick, Lawrence &c which have furnished, as we have heretofore, more than our quota of men: and we insist upon having something done for the discharge of the men drafted from this Town forthwith. We sent by Mr Davis a list of all the men that have gone from this town, the Reg and Co. to which they belong. If you desire it we can send another if that has not been preserved for reference. Genl John J. Perry is acquainted with the particulars of the case and I will refer you to him for further information in regard to myself &c &c. We Shall expect credit for every man furnished, and shall consent to nothing short of the same privileges granted to towns in Mass. & N. Hampshire which have done just what we have & no more — the overplus of men furnished heretofore on our quota to be discharged from the draft.

If the same efforts are made by our authorities that have been Made by officials in other States I have reason to beleive [sic] that all will made satisfactory to the people.

Respy Your Obt Svt,

Jeremiah Bartlett45

Bartlett's request did not save Record and Russell from the

draft, but the issue he raised was eventually resolved by higher powers.

In answer to a similar complaint, his superior in Washington assured

Maine's adjutant general that "the Government is abundantly able to

accept the excess of the liberal towns as a surplus to be placed to

their credit," and indeed, in February 1864, federal policy changed to

allow districts and towns to count their excess enlistments against

future calls.46 No more men would be drafted from Greenwood.

O. K. Yates

On October 17, 1863, came a new call for troops, and two weeks later a directive from the state. Town selectmen were invited to recommend recruiting officers, to be paid $25 for each veteran he reenlisted, $15 for each new recruit. Octavius K. Yates had been, by his own account, the second man to enlist in the Auburn Artillery at the outbreak of hostilities, but did not follow when his company was mustered into the First Maine Regiment. He had in 1862 been elected a junior officer of Greenwood's militia company, and on November 16 requested of Augusta "the appointment as Recruting [sic] Officer, as I think I could enlist a sufficient number of men to fill the Town’s quota."47 He also requested forms sufficient to enlist thirteen men. The provost marshal authorized him to proceed, but the selectmen of Greenwood did not recommend his appointment until December 13, and advised Yates to again request authority from the state. Yates had in the meantime signed up twelve men, but failed to send in a list of recruits as required. He blamed his oversight on a notice having been sent to the wrong post office.

I trust this will be a sufficient excuse, at [the Locke's Mills] office we get the mail daily and at the Greenwood Office which is at the extreme part of the Town only twice a week.48

The list he had neglected to send was attached to his letter of December 14, and bore the names of Charles E. Dunn, Darius Richardson, David M. Morgan, Hartwell Keaton, William Keaton, Samuel S. Millett, Hugh Berry, George E. Howe, Michael Gorman, Clariton A. Blake, Albert A. Cross and Reuben B. Bean. Howe and Bean were to serve on Bethel's quota, the others on Greenwood's. Each was promised a bounty of $300 from their respective towns when mustered in.

The Keaton brothers both became privates in Company C, Twenty-Ninth Maine Infantry, on December 30. Within a year the younger brother, Hartwell, would be dead from disease. Charles E. Dunn enlisted for three years' service in Company M, First Maine Heavy Artillery. He would suffer wounds the following summer that left him lame the rest of his life. David M. Morgan joined Company M as well, and would also be wounded, May 19, 1864, near Fredericksburg Pike, Virginia. Samuel S. Millett served with the Third Battery, Maine Mounted (Light) Artillery.

Michael Gorman had enlisted in the Fifth Maine in 1861, but was never mustered in. Nor would he be accepted into service in 1863, after signing Yates's enlistment roll. Gorman's petition for naturalization, dated April 18, 1861, stated that "he was born at Longford in Ireland in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and six."49 At age fifty-seven years, he may have been rejected by the examining surgeon.50

Like Gorman, Darius Richardson had enlisted in the Fifth Maine two years before, but failed to appear at mustering in. He was recruited again by Yates, and collected his bounty upon entering the Seventeenth Maine Infantry on December 26. Richardson was listed as forty-six years of age in the 1860 census—too old even then to be accepted into service. A month after his mustering in, a board of inspection convened at regimental headquarters determined that Richardson was "disabled by reason of old age, Mental and Physical disability" — that "Mentally this man is 'non compus mentis' and physically unable to go through with the manual of arms."49 Richardson testified before the board that "undue influences had been brought to bear upon him by his wife and another person to induce him to enlist, they desiring and intending thereby to secure his bounty for themselves." The unnamed co-conspirator was presumably Octavius K. Yates.

Despite the findings of the board, Richardson was not discharged. He remained with his company, was "taken sick with the jaundice," and died in the Second Corps Hospital at City Point, Virginia, June 28, 1864.

In supporting Permelia Richardson's application for a widow's pension, Greenwood selectmen Willard G. Whittle and Isaac Flint denied the late soldier's accusations, saying that Richardson had voluntarily enlisted and received his bounty "in person." They testified further that O. K. Yates received just $15 for recruiting Richardson, and "has always been a man of good character and reputation." To the question whether Richardson's age provided any grounds to deny the application, pension agent George F. Emery argued that "if the soldier was 'old,' he was not too old for the government to accept him gladly as a soldier."

Suspicions regarding Octavius K. Yates lingered in town even after the end of hostilities. Mrs. E. A. Etheridge of Locke's Mills would write to the adjutant general in May 1865 on behalf of a Bethel man whose son had died in the service a year before, and had been recruited by Yates. The father had not received his son’s town bounty, and did not know whether he had been credited to Bethel or to Greenwood. "Of course," Mrs. Etheridge asserted, "we think Mr Yates recieved the mon[e]y and retained it as he has in other cases."52 Yates had by that time completed his recruitment services and been appointed a United States Detective. While in Washington testifying in a government case, Yates secured a ticket to Ford's Theatre the night of President Lincoln's assassination — a story he would enjoy telling till the end of his days. He would later practice medicine at Locke's Mills and West Paris.

The Last to Join the Fight

Eight companies of cavalry were organized at Augusta in the early months of 1864. These were first attached to the First D. C. Cavalry Regiment, and later incorporated into the First Maine Cavalry. George W. Bryant and Cyrus A. Buck enlisted in Companies G and I, respectively, on Greenwood's quota. George G. Howe, William Whitman and Cornelius M. York, all of whom had previously served with the Fifth Maine Infantry, rejoined the fight as cavalrymen in this regiment. Both Buck and Howe would die of disease in January 1865. York would survive his second tour of duty only to die in 1871 while at work in Bethel, having fallen from a load of hay and been impaled by a pitchfork.

Albert A. Cross, James B. Currier, Damon LeBaron, Simeon Morgan and Wilber F. Whittle joined the Thirty-second Maine Infantry as new recruits, and Elijah Libby as a veteran. Whittle died of typho-malarial fever at Stanton Hospital in Washington, D. C., July 6, 1864. Damon LeBaron's father Nathaniel was serving as a wagoner with the Seventeenth Maine when his son enlisted, and was stationed near Petersburg, Virginia, when Damon died of disease at Augusta, August 30, 1864. Cross and Morgan were taken prisoner July 20, 1864, at Cemetery Hill in Petersburg, and died in prison the next winter at Danville, Virginia. Consider Cole, who had reenlisted from Paris in the same company, was captured the same day, but was paroled before his death.

Three more young men enlisted from Greenwood in 1864, but only one could honestly report his age. Charles H. Hobbs, whose family was living at the southern edge of Greenwood, enlisted in Company H, Maine Militia Light Infantry Volunteers, in April. The company was stationed at Fort McClary in Kittery for just sixty days, making Charles an honorably discharged veteran before his sixteenth birthday. In September, less than a month after the death of his mother, eighteen-year-old James Libby was mustered into Company G, Sixteenth Maine Infantry. His younger brother Richard, who was perhaps fifteen years old, followed James to Auburn and signed up for two years' service in Company B of the same regiment. He died from measles, January 29, 1865, at Division Hospital in Petersburg, Virginia.

Twenty-one Oxford County towns and plantations were deficient in their quotas and subject to a draft in late September 1864, but Greenwood was not among them. In June the town had an excess of six enlistments, which helped satisfy its quota after the call of July 18.

Enlistments in Greenwood slowed in the final months of the war. Greenwood was reported in February 1865 to have a quota of eight men, and a credit of ten. With no fear of being drafted, Byron V. Bryant, Charles C. Bryant, Albion K. P. Currier and William E. Starbird joined the Eighteenth Company of Unassigned Infantry (later Company I, Twelfth Maine Infantry (new organization)) in March 1865. They were accompanied by Albion's father, James B. Currier, who had been discharged from the Thirty-second Maine for a physical disability the previous year. Nelson S. Swift, not yet eighteen years of age, was mustered into Company H, Twelfth Maine Infantry. He was the eldest son of Cyrus Swift, who had succumbed to disease in Louisiana in 1862.

A Final Accounting

Love of country was often enough to encourage a reluctant man to volunteer, but where this would be burdensome to his family, an increase in federal, state and town bounties was sometimes required. In October 1863 a new recruit could earn $357 in federal and state bounties for joining an organization already in the field, with $130 (including one month's wage) paid in advance. For the veteran soldier, whose experience could help clear a new company's path to the battlefield, there were financial incentives totaling $502 to enlist in one of the regiments or batteries not yet fully organized. A town's bounty could add perhaps $200 to this total.

At a town meeting held July 19, 1864, Greenwood agreed to raise $50 a piece for recruits, to fill the President's most recent call. This was increased to $300 in August. The town authorized the selectmen "to procure loan or otherwise the money which may be necessary to pay for recruiting men to fill the call of July 18th, 1864 and also to pay for recruiting for future calls if in their judgment necessary." Matthew Lane from Halifax, Nova Scotia, and James Sullivan from Dublin, Ireland, may never have set foot in Greenwood, but they were on the town's payroll when they were mustered into the service of the United States in December 1864.

Additional aid was often needed by the families of enlisted men in their absence, by those who had suffered illness or injury while in the service, and by the survivors of fallen soldiers. An article to see whether "the town will Raise Enny money as means to Support the Soldiers familys" was passed over at Greenwood's town meeting on March 3, 1862. Two weeks later, though, an act "in aid of the families of Volunteers" was signed into law in Augusta. The act required that the selectmen provide financial support to the dependent families of soldiers in active service, and, at their discretion, to the families of casualties of war. Towns would be reimbursed by the state seventy-five cents per week for a dependent wife, parent or sister, and fifty cents for each child, not to exceed ten dollars per month per family.53 To satisfy the requirements of this law, Greenwood on April 12 voted to raise $300. They would raise much more in years to come.

Greenwood's selectmen were obliged to help where help was needed, but had to ensure that the town would be reimbursed. Stephen Mitchell had lived in Paris before the war, and enlisted from that town in the Fifth Battery, First Maine Mounted (Light) Artillery. His family came to Greenwood around the time of his enlistment in 1861. He was the father-in-law of George W. Patch, and his son Peter Jordan Mitchell served from Greenwood, rose to the rank of first lieutenant, and died of wounds sustained in battle, November 12, 1864, at Martinsburg, Virginia. Stephen was listed both as discharged at Augusta upon the expiration of his three-year term, December 4, 1864, and as mustered out at Augusta, April 5, 1865. Willard Herrick wrote to the adjutant general, by order of the selectmen, August 23, 1865, to determine which date was correct: "Mr. Mitchell sayes that he is sure that he was discharged on the 4th day of April 1865 but as he has not yet shown his discharge and says that he does not know but he has lost it we wish to have something from you to show when the State Aid should be stoped."54

Aid would eventually be stopped for all families, replaced in 1868 by a state pension program for disabled veterans, widows, orphans and dependents, to pay no more than eight dollars per month per family.

Such Heroes are Scarce

A complete account of Greenwood's contributions to the war effort would fill a large volume, and would mention not just those men who lived there during the war years and served on its quota, but also those natives of Greenwood who served from other towns, and those veterans who settled in Greenwood after the war. It would include the unique details of each soldier's experience — of the sacrifices made necessary by his decision to enlist, and of the physical and emotional scars that resulted.

The available records provide clues to these last details. An 1890 census of Union veterans and widows asked Greenwood's aging soldiers what disabilities incurred during their service still afflicted them. Nathaniel LeBaron suffered from chronic rheumatism and heart trouble, and used "crutches most of the time." Orin Ring, who had come to town from Casco, had deafness in both ears, and Charles Lapham from Bethel complained of a ruptured midriff. (During the war, a tree had fallen on Lapham's tent while he was lying in it.) Andrew J. Ayer was blind in his left eye, which he attributed to sunstroke suffered while in the army. John Lyden had "Lost two fingers on one hand." Another resident of the Irish Neighborhood, Patrick Flaherty, had been "Insane when he came home." Every neighborhood in Greenwood had at least one aging man whose ailments or broken gait recalled his long-ago service.

Another Greenwood soldier claimed no disability upon his return, but his life was no less marked by the war.

Locke's Mills, Jan. 1865.Mr. Editor: It is not uncommon in these days for Newspapers to notice the arrival of officers and soldiers, who have been absent one or two years, or more, from home, and done their country service. I always like to notice such things, especially when the parties are really meritorious. Mr. Abner H. Herrick of this place, who enlisted as a private in the 5th Maine Regiment, Jany. 6th, 1862, returned home last Saturday, after serving out his three years. He has been in twenty battles, and over forty skirmishes — been hit six times, without serious injury. In the battle of Antietam, with his blanket on his back, thirty-two bullet holes were made in it. What is more singular still, he was never absent from his Regiment, for the whole time of three years, a single day — was never in a hospital, nor an ambulance, a day. There are but few of the old fifth left to tell the sad tales that Mr. Herrick can relate, or who can say that they served their time out, without being sick a day, or having a furlough. I send you a list of battles in every one of which he fought.

Seven days before Richmond, under McClellan, Second Bull Run; Crampton's Pass; Antietam; Fredericksburg, — First; Fredericksburg, — Second; Salem Church; Gettysburg; Rappahannock Station; Mine Run; Wilderness; Spotsylvania [May] 10th; Spotsylvania [May] 12th; Coal [sic] Harbor; Petersburg; Winchester; Fisher's Hill; Cedar Creek; Locust Grove. Such heroes are scarce, and if the shoulder straps seen flaunting in the streets were oftener worn by such men, the days of the rebellion would soon be numbered.55

Corporal Herrick had lost one young son while away in the service, and had gained another — born two months after his enlistment. After introducing himself to the boy — now nearly three years of age — he settled back into civilian life on the farm his wife's parents had established near Round Pond. For Abner, as for the other veterans of Greenwood, there was work still to do.

Notes

1"Intimate Recollections and Relics of a National Hero — Gen. George Beal of Norway," Lewiston Journal Magazine Section, May 29, 1915.

2Gov. Israel Washburn Jr. to Simon Cameron, Secretary of War, April 26, 1861, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (hereinafter The War of the Rebellion), Series III, 1:119.

3William B. Lapham, My Recollections of the War of the Rebellion (1892), p. 37.

4Capt. Moses Houghton to Adj. Gen. John L. Hodsdon, May 7, 1861, Box 31, Woodstock folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives.

5Capt. Moses Houghton to Adj. Gen. John L. Hodsdon, May 11, 1861, Box 31, Woodstock folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives. W. J. Hardee's Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics was first published in 1855, and remains a valuable resource for Civil War reenactors.

6Capt. Moses Houghton to Adj. Gen. John L. Hodsdon, May 17, 1861, Box 31, Woodstock folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives.

7Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine, for the year ending December 31, 1861 (1862), Appendix A, p. 20.

9William B. Lapham to Adj. Gen. John L. Hodsdon, Sept. 21, 1861, Box 31, Woodstock folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives.

10William B. Lapham to Gov. Israel Washburn, Sept. 23, 1861, Box 31, Woodstock folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives.

11Box 85, Companies Unattached - Woodstock folder, Civil War Regimental Correspondence, Maine State Archives. This folder contains no actual correspondence, but rather three rolls for Houghton's company. Other members of the company came from Woodstock, Paris, Norway, Bethel, Hamlin's Gore, Milton Plantation, Canton, Rumford, Andover, Roxbury and Mexico.

12Capt. Moses Houghton to Adj. Gen. John L. Hodsdon, June 17, 1861, Box 15, Greenwood folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives.

13Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine, for the year ending December 31, 1861 (1862), p. 13.

14William B. Jordan, Red Diamond Regiment: The 17th Maine Infantry, 1862-1865 (1996), p. 3.

15Capt. Moses Houghton to Adj. Gen. John L. Hodsdon, July 16, 1861, Box 15, Greenwood folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives.

16Oxford Democrat, Aug. 2, 1861. The Day Book was a notoriously secessionist newspaper then published in New York. Publication was suspended in September 1861 when it was denied the further use of government mail facilities.

17Oxford Democrat, Sept. 6, 1861.

18William B. Lapham, The History of Woodstock, Maine (1882), p. 114.

19Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine, for the year ending December 31, 1861 (1862), p. 14.

20Oxford Democrat, Oct. 18, 1861.

21Oxford Democrat, Nov. 8, 1861.

22Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine, for the year ending December 31, 1861 (1862), Appendix A, p. 10.

23Lewiston Daily Evening Journal, Oct. 18, 1861.

24Oxford Democrat, Oct. 18, 1861.

25In his History of Bethel, Lapham tells of finding Consider drunk in a Bethel schoolhouse one cold night, and reports that "Consider enlisted and went to the war and never returned, which was, perhaps, just as well. He could not resist an appetite long indulged and which was hereditary" (p. 440). It is worth noting that Consider Cole enlisted of his own volition, though old enough to escape both enrollment and any contemplated draft, served the length of the war, and (according to his pension file) used a portion of his enlistment bounty to provide support for his aged mother. Meanwhile, the younger and more temperate Dr. Lapham spent much of 1861 and 1862 pleading for a commission and recruiting other men to be sent off to battle.

26Edwin B. Lufkin, History of the Thirteenth Maine Regiment (1898), p. 5.

27Kingsbury J. Cole to Secretary of State J. B. Hall, May 11, 1862, Box 15, Greenwood folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives.

28Joann P. Swift, widow's pension application no. 28,446, certificate no. 40,724, service of Cyrus Swift.

29Sarah Morgan, mother's pension application no. 127,969, certificate no. 129,613, service of George W. Morgan.

30This and other Lory N. Fifield letters from "Four Civil War Letters," transcribed at https://rbrown.incolor.com/roots/notes/notes3.html. (archived)

31Sarah Morgan, mother's pension application no. 114,793, certificate no. 119,577, service of Samuel Morgan.

32U.S. Adj. Gen. L. Thomas to the Governor of Maine, Dec. 25, 1861, The War of the Rebellion, Series III, 1:759.

33Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine, for the year ending December 31, 1862 (1863), Appendix A, p. 2.

34U.S. Adj. Gen. L. Thomas to the Governor of Maine, May 21, 1862, The War of the Rebellion, Series III, 2:61.

35Gov. Washburn to U.S. Adj. Gen. L. Thomas, May 22, 1862, The War of the Rebellion, Series III, 2:63.

36Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine, for the year ending December 31, 1862 (1863), Appendix A, p. 15.

37Gov. Israel Washburn to Sec. of War E. M. Stanton, May 26, 1862, The War of the Rebellion, Series III, 2:76.

38Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine, for the year ending December 31, 1862 (1863), Appendix A, p. 14.

39Charles H. Milliken, invalid pension application no. 34,128, certificate no. 43,356.

40Jeremiah Bartlett to Adj. Gen. John L. Hodgdon, September 20, 1862, Maine State Archives. Images and transcription at https://www.maine.gov/tools/whatsnew/index.php?topic=arcsesq&id=147850&v=article. (archived)

41Maine Supreme Judicial Court Records, Oxford County, volume 10, page 378.

42Willard Herrick, William Richardson and Calvin Crocker, to the Adjutant General's Office, Sept. 7, 1864, Box 15, Greenwood folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives.

43Oxford Democrat, July 24, 1863.

44Harry A. Packard, "One of Maine's Old Revolutionary Families — The Noyeses," Lewiston Journal Illustrated Magazine Section, May 7, 1927, p. A1.

45Jeremiah Bartlett to Gov. Abner Coburn, Aug. 5, 1863, Box 15, Greenwood folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives.

46Provost Marshal General James B. Fry to Adj. Gen. John L. Hodsdon, Jan. 13, 1864, The War of the Rebellion, Series III, 4:28.

47O. K. Yates to Adj. Gen. John L. Hodgdon, Nov. 16, 1863, Box 15, Greenwood folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives.

48O. K. Yates to Adj. Gen. John L. Hodgdon, Dec. 14, 1863, Box 15, Greenwood folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives.

49Maine Supreme Judicial Court Records, Oxford County, volume 9, page 94.

50Another Greenwood resident too old to serve, Artemas Felt, had signed George W. Patch's enlistment roll in 1861, claiming to be forty-four. He was in fact sixty-one, and was rejected by the surgeon.

51Permelia Richardson, widow's pension application no. 61,507, certificate no. 125,842, service of Darius Richardson.

52Mrs. E. A. Etheridge to Adj. Gen. John L. Hodgdon, May 27, 1865, Box 15, Greenwood folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives. The writer was Elizabeth A. (Child) Etheridge, wife of Martin R. Etheridge. The soldier, Lewis Powers, served on Bethel's quota.

53Public Laws of the State of Maine from 1861 to 1865, Inclusive (1865), p. 94.

54Willard Herrick to Adjutant General, Aug. 23, 1865, Box 15, Greenwood folder, Civil War Municipal Correspondence, Maine State Archives.

55Oxford Democrat, Jan. 3, 1865.